Prof. Paul Bloom on Freud:

Prof. Paul Bloom is a developmental psychologist, and not Freudian scholar. As a hobby reader of psychoanalysis, I wanted to hear about Freud from someone who has academic expertise in the field of psychology. Liked simplicity in his explanations, hence sharing.

His blog small potatoes is worth reading.

With that said, here is excepts from Prof. Paul Bloom.

Q: if you could have dinner with any researcher living or dead who would it be?

Paul Bloom: I would go for Sigmund Freud. I disagree with a lot of what the man said but he was by all accounts brilliant, charming and just a fascinating person.

Although Freud has some terrible ideas, some of the dumbest ideas that ever passed through somebody's mind, he had some brilliant ones as well and I think his big pitch for a dynamic unconscious, the idea that we don't really know why we do what we do has enormous staying power and is now part and parcel of of psychology and he deserves a lot of credit for it.

Q: What are some issues you have with Freud?

He was also a beautiful writer, nominated for the Nobel Prize and winner of other prestigious literary awards, a well-known scholar in his time, he was an incredibly brave and important thinker. His books, such as my favorite, Civilization and Its Discontents, brim with clever thoughts, and have sparked all sorts of valuable insights in other writers and thinkers.

You could criticize him for his overemphasis on sex, and I think you should. I think some of it is kind of silly. But he did recognize female sexuality, a topic that was forbidden for many. He recognized that adolescent and even childhood sexuality, in some ways, take on a different meaning. When you're talking about children, crushes and desires exist.

One way to put it is that, for Freud, everyone was a pervert. If everyone's a pervert, nobody is a pervert.

The biggest, most mind-blowing shock to our egos comes from school of psychoanalysis, where he says we are not masters of our fate. We might think that we fall in love, we have an enemy, we start a podcast, and we know why we're doing them. And Freud came in and said, 'You might think you know it, but you don't.' We're driven by forces beyond our control.

A lot of details he had to say about there is I think are wrong, but the general idea – which wasn't his, even he acknowledged, but the idea is tremendous force. And now it's it's now it's accepted by most everybody.

I don't have a chapter on Carl Jung because I don't think somebody who's interested in Psychology needs to know about Carl Jung[1]

I’m surprised that he doesn’t seem to appreciate Jung so much, not sure if he had time to read Jung/phenomenological literature. This podcast prompted me to briefly take a look at his new book Psych: The Story of the Human Mind, excerpts below.

Q: What should we make of Freud’s theory? How much of this is true? How much of it is good science?

One concern builds from an idea of the philosopher Karl Popper. This is the notion of falsifiability. Popper argued that one thing that distinguishes science from non-science is that scientific theories make claims about the world that run the risk of being proven false.

Now, few philosophers today believe that falsifiability is the absolute criterion through which you can distinguish science from non-science. It’s more complicated than that. There is no single observation that could falsify the germ theory of disease, say. But still, there is a real insight here: We should suspect theories that cannot be proven false. The physicist Wolfgang Pauli famously derided the work of a colleague by saying, “He’s not right. He’s not even wrong,”

Overall, Freudian theory is either vague or unsupported by the evidence. This is why we no longer study Freud in most psychology departments.[2]

Post thoughts:

One of the main criticism against Freud’s psychoanalysis was from Karl Popper, a philosopher of science, who criticised the psychoanalysis for lack of verifiable claims. Well summarized here in this [3] blog. Poppers criticism seems fair, given that psychoanalysis explains human behavior but fails terribly in prediction.

I suspect that there has been some misunderstanding.

Why there is a debate if psychoanalysis is scientific or not, but no debate if morality or ethics are scientific?

How did they come to conclusion that falsifiability is the right tool to apply to psychoanalysis?

Falsifiability essentially means a theory cannot be used for prediction, Is moral theory predictive? No. Does this make moral theory invalid? No.

Prediction is important to science. Why bring scientific instruments to understand philosophy?

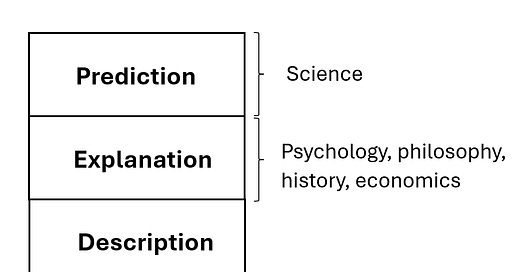

Human behaviour isn’t scientific or rational. Psychology, philosophy, economics, history are explanatory theories, not predictive.

Description vs explanation

Psychiatrist Jonathan Shedler argues that DSM - the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the so-called bible of psychiatry, provide only description.

Diagnoses listed in the DSM—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the so-called bible of psychiatry—do not cause anything. They are not things. They are agreed-upon labels for describing symptoms. Generalized anxiety disorder means a person has been anxious or worried for six months or longer and it’s bad enough to cause problems—nothing else.

The diagnosis is description, not explanation. Psychiatric diagnoses are categorically different because they are merely descriptive, not explanatory. It's not that we don't know their causes yet. It's that DSM diagnoses cannot speak to causes, now or ever. The DSM was not designed to speak to causes, only describe effects.[4]

References:

Psych: The Story of the Human Mind (2023), chapter on Freud

It’s Impossible to Justify Predictions from Evidence - Good summary of criticism of Popper against Freud.